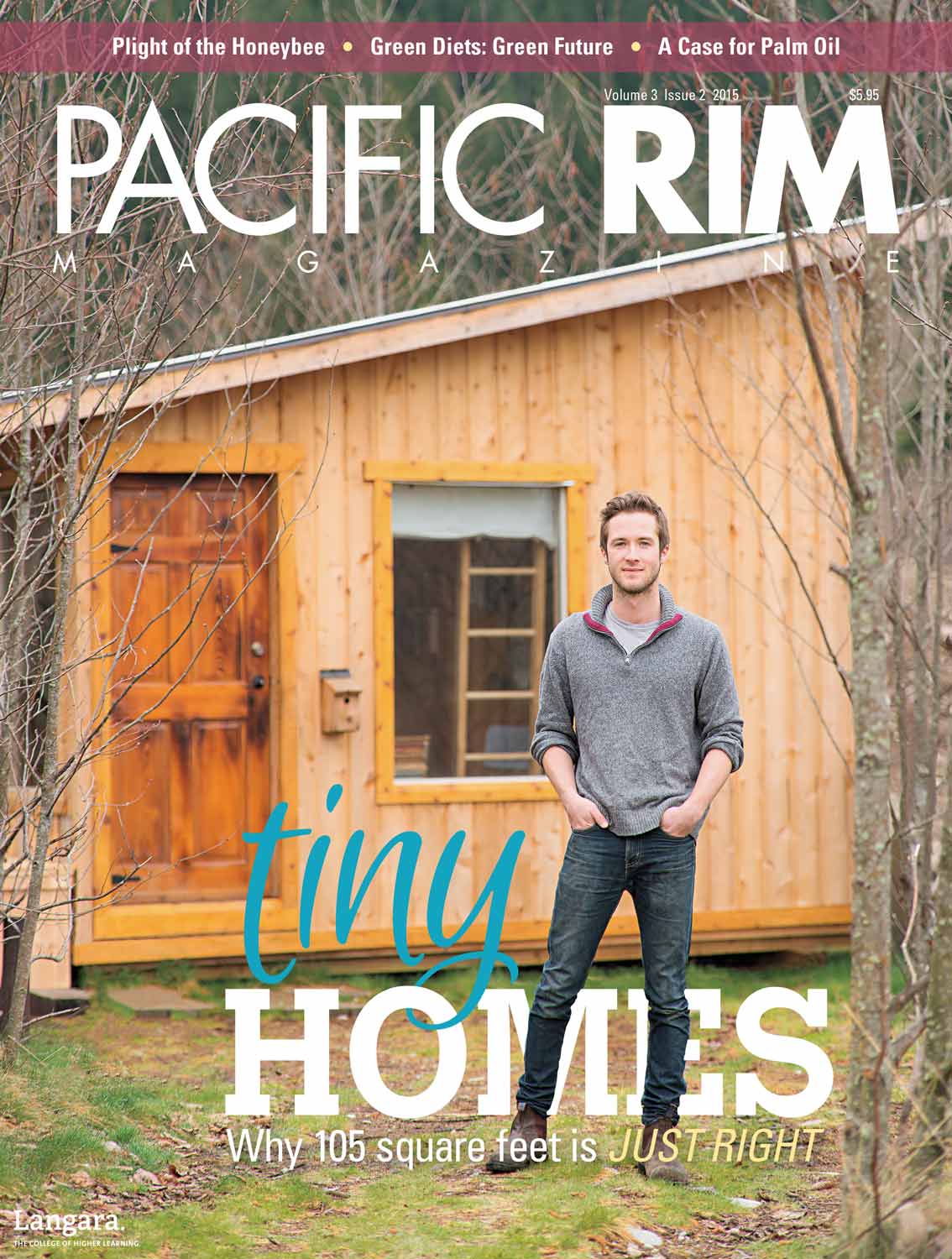

Exhausted, sick, and malnourished, residents of a farm in rural British Columbia dream of the simple life in the city, where food abounds and there’s plenty of room to start a family. The countryside is usually depicted as a relaxing, wholesome retreat from city life. However, this stereotype has been reversed in recent years — for the bee population, at least.

The decline of bees since the 1990s is of great concern, and has been extensively reported on. Threats such as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), mites, and habitat loss have resulted in the death of a large number of bees, particularly commercial honeybees.

However, in the last five years, urban beekeeping has experienced a boom. Major cities worldwide are legalizing it. Rooftop hives are becoming a part of urban greening plans, and a mainstay atop restaurants, cafés, and luxury hotels. In 2014, The Economist reported that “despite the stereotype of beekeepers as luxuriantly bearded eccentrics, many newbies are young — women are particularly keen.” So why is it that while bees are being welcomed in new environments, their numbers are still declining?

Bees in Crisis

While urban bees are living it up in custom-built homes on the Paris Opera House, Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City, and Fortnum & Mason department store in London, England, rural bee populations have a decidedly different lifestyle. Their limited natural habitat is being cleared for agricultural use or urbanized, and farmers are using insecticides such as neonicotinoids on their crops. In the low levels found on agricultural crops, neonicotinoids prevent bees from foraging properly, stunt their development, increase their susceptibility to disease, and damage their capacity for memory and learning. In high levels, neonicotinoids can cause death within 48 hours; they are one of the suspects in the investigation of CCD.

A 2013 paper published in Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability reports that in less than 20 years neonicotinoids have become the most widely used insecticides around the world, accounting for more than 25 percent of the global insecticide market. They stay in the soil and water after use and are absorbed by the next crops planted, or by neighbouring wild plants, in the years following their application.

Conditions are less than ideal for bees on rural farms. Farmers clear their land of all native plants, leaving only their crops to be pollinated. This means that the bees consume pollen and nectar from only one variety of plant, which is not nutritionally adequate. “It’s like eating Kraft Dinner for a month,” explains Brian Campbell, a Vancouver apiarist and the founder of The Bee School, a certificate program for aspiring beekeepers.

The bees will continue to eat the available food, but it isn’t healthy. The commercial colonies die off, as do the native bees in the area. Campbell tells the story of his friend, a blueberry farmer, who used to require one hive of imported honeybees per acre to pollinate his berries. Now, he needs five. “He didn’t realize that the native bees were helping him out,” says Campbell.

The decline of wild bee populations has affected farmers around the world. In 2012, Dave Goulson, a professor of biology at the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom, reported that areas of Southwest China were devoid of wild bees due to the overuse of pesticides and the destruction of natural habitats. As a result, owners of local apple and pear orchards were forced to pollinate by hand, painstakingly carrying paintbrushes and pots of pollen from tree to tree.

Embracing Our Pollinators

Vancouver legalized urban beekeeping in 2005. According to The Vancouver Sun, the number of bee colonies in Metro Vancouver rose almost 400 percent between 2001 and 2011. Hives have been built atop the Vancouver Convention Centre, City Hall, and the Fairmont Waterfront hotel. City hives are tucked away, often on rooftops, because urban beekeepers feel some pressure to keep them hidden; many people are still uncomfortable with the idea of bees living nearby.

This feeling is amplified in many Asian countries, where bees are often seen as unwanted pests. The New Paper in Singapore spoke to Thomas Lim, a local beekeeper. Lim maintains beehives to pollinate his gardens, but he needs to conceal them; the Singapore residents interviewed said that they would likely contact a pest control company if they found bees living nearby. In 2013, a pest control company accidentally destroyed one of Lim’s two successful hives. They doused the whole thing in insecticide, killing thousands of bees inside.

However, individuals in some Asian cities are embracing urban beekeeping as a way to connect environmental health with business. In 2013, Hannah Smith, who holds a master’s degree in Asia Pacific Policy Studies, identified some examples for the Asia Pacific Memo: in Tokyo, the Yaesu Book Center keeps a rooftop apiary and sells the honey in its café. In Seoul, urban beekeeping movements offer classes on candle making, and education about bees. In Hong Kong, resident Michael Leung maintains a number of bee farms and designs products and services for urban beekeepers.

Having bees in cities is beneficial to broader sustainability initiatives. Noah Wilson-Rich, a Boston-based beekeeper, gave a TED Talk in 2012 on urban beekeeping. He lamented the proliferation of tarpaper roofs, which reflect heat back into the atmosphere, in New York City. He suggested an increase in green roofs, which could be used to grow food and to house bees for pollination. This would reduce both transportation costs and greenhouse gas emissions from food production.

Urban bees have adapted admirably to their environments. Scott MacIvor, a PhD candidate at York University in Toronto, discovered that some wild bees have been using detritus from urban life in their nests. In the journal Ecosphere, MacIvor reported that instead of plants, bees in the Toronto area were using materials like window caulking and plastic bags to build their homes. Encouragingly, these man-made materials did not seem to have any adverse effect on the bees; they all lived to adulthood.

An Uncertain Future

The disparity between the health of urban and rural bees has been observed and documented by concerned beekeepers like Wilson-Rich. He supplies bees for both environments; his urban bees have an overwinter survival rate of 62.5 percent, compared to just 40 percent for rural bees. The honey yield differs, too. In the city, a hive in its first year averaged almost 12 kilograms of honey, whereas a hive in the countryside produced roughly 7.6 kilograms.

While urban bees are faring better, their future health is not assured. Many cities are reaching a level of saturation; there are not enough plants to provide adequate nutrition for growing bee populations.

“If you’re concerned about the status of bees, take up gardening. Plant flowers,” suggests Campbell. An abundance of flowers not only provides food for local bees, but also ensures genetic diversity. In a fractured urban environment, where gardens are divided by concrete towers, bees might only associate with others from their own colony. Without sufficient genetic diversity, colonies stop producing female bees, and the hive dies off.

Education is another way to help bees in the long term. Dick Scarth, a Vancouver beekeeper, is teaching elementary school students how to build nests for local mason bees. He has developed a way to build homes for the bees using recycled materials like scrap paper and milk cartons. Once he has helped students construct the nests, they mount them on their houses or near their schools so they can watch the bees at work. Scarth suggests that the best way to improve the future for bees is to get to know them. “Get [young people] involved with bees hands on — a safe bee, in this case: the orchard mason bee.”

Taking Action

The increase in urban beekeeping is a good sign that we are beginning to take the plight of our pollinators seriously. The next step needs to be writing protective measures into law. Hannah Smith was shocked to discover how little was being done to protect the declining bee population, especially given bees’ vital role in

food production.

“Legislators and city planners need to understand that cities need to be ‘bee friendly’ — with ample opportunities for keeping hives, and plenty of places for bees to feed,” Smith writes in an email interview. “Beekeeping needs to be woven into wider city sustainability initiatives and become an intrinsic part of living in a green city.”

Dick Scarth believes that education will help to get the necessary legal steps taken to protect our pollinators. “If we can get kids, students, even adults, to be interested in this, we’re going to tell [the government] that we’re killing our bees, destroying our food sources, by using chemicals that harm them.”

He goes on to say, “That’s the big picture. The small picture is a lot of fun. Isn’t it amazing that given about 20 seconds of your time, and recycled materials, you can provide pollination for trees and flowers, and learn about the natural world?”