Son Ngoc Samouth sips a glass of strong French coffee as he stares out at the rainy, garbage-filled streets of Phnom Penh. He seems lost in thought as he describes, almost by rote, the day that a landmine tore through his body, ripping off most of his left leg and leaving him blind in one eye. Samouth is a Cambodian; he says he’s one of the lucky ones.

At the beginning of the last rainy season, he was plowing the field at his small farm outside the northern town of Siem Reap. It was an area known for violence between the guerrilla army of the Khmer Rouge and the military forces of the government of Cambodia. “It was like any other day. I was getting the field ready for the first rice crop. I’ve plowed that field hundreds of times,” he says.

He doesn’t remember much about the explosion that changed his life. He says he remembers being knocked over and not understanding why. “It’s hazy. I was walking beside the [water] buffalo, about 10 paces away, when I kicked something under the water. After that I was lying on my back staring up at the sky. I had no idea I was even hurt,” says Samouth.

He doesn’t remember much about the explosion that changes his life. He says he remembers being knocked over and not understanding why.

Samouth was lucky because his wife heard the blast and came to his aid. She rounded up Samouth’s two brothers, who slung him over the back of the family’s water buffalo and took him to the United Nations’ hospital in Siem Reap. Unlike Samouth, many landmine victims don’t survive. They trigger mines when they are out of earshot and bleed to death where they lie.

Unusable Land By Minefields

The landmine that Samouth set off could have been laid 24 hours-or 24 years-before it crippled him. After a conflict has ended, anti-personnel (AP) mines can remain in the ground for years, even decades. Today, 28 per cent of Libya’s arable land is unusable due to minefields that were planted during the Second World War. It is no different, and perhaps worse, in Cambodia.

Cambodia Has The Largest Population Of Disabled People

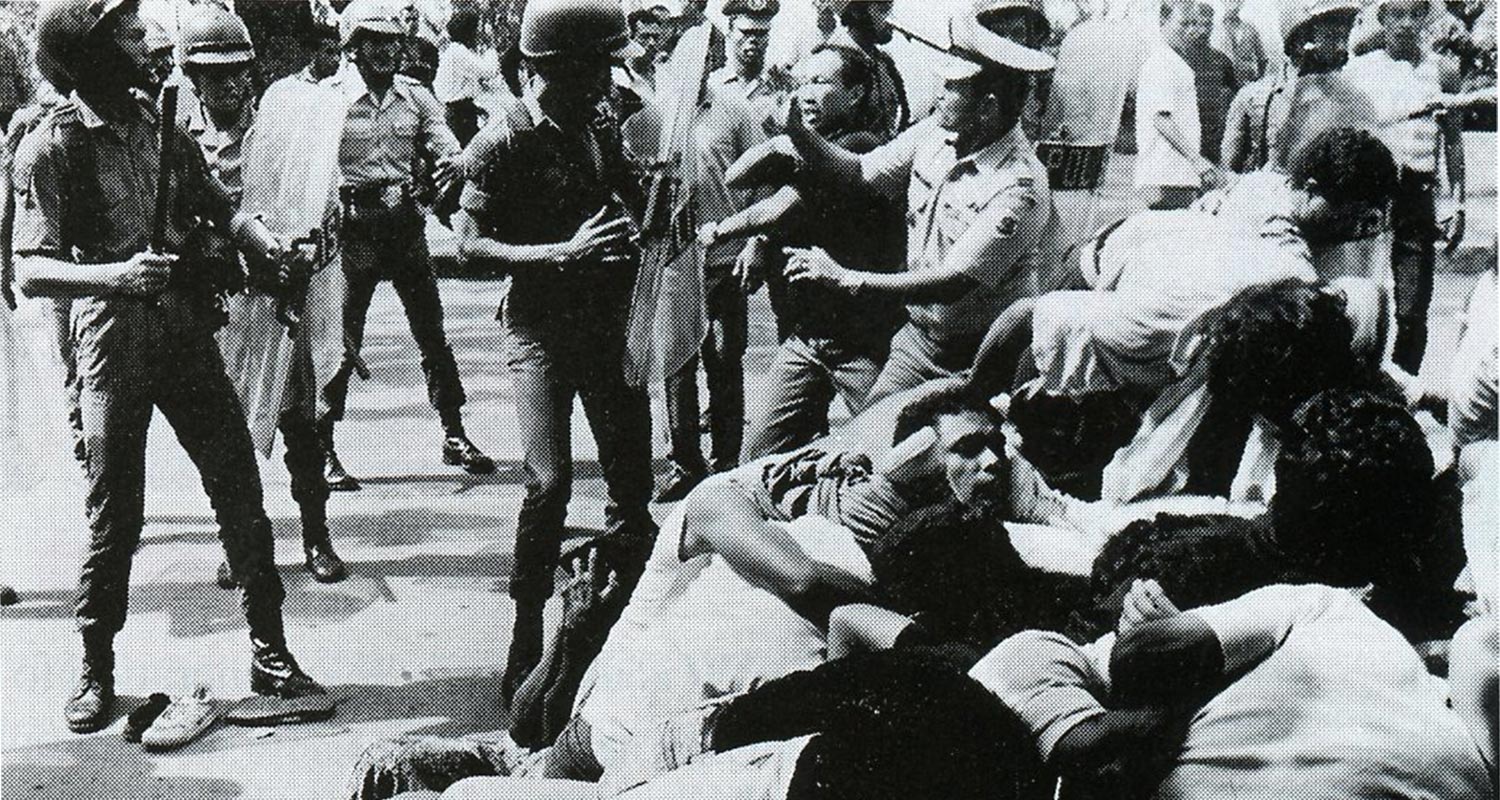

Two decades of war have left a tragic legacy. The UN estimates there are between 6 and 10 million landmines buried in Cambodian soil. Their by-product is 200300 amputations per month, 90 per cent of which are performed on civilians. With one person out of every 230 crippled, Cambodia has the highest percentage of disabled people in the world.

The damage, however, goes beyond the farmers in the fields. Random scattering of AP mines, with inadequate mapping of minefields, has left a large proportion of Cambodia’s farmlands unusable. It has ruined the country’s ability to provide for itself.

Cambodia is an agrarian society. During the last 20 years, much of the country’s farming infrastructure has been destroyed, either collaterally or as a direct war aim. Both the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Peoples’ Army have extensively mined farmland to cut off food supplies to each other. The impact has been wide-spread famine and further destruction of an already devastated economy.

Even when fields are mapped or marked there is no guarantee of safety. The heavy monsoon rains can move mines many kilometres from their original site, or bury them deeper in the mud, making a field appear to be not mined. The result is that some fields have been mined many times. The layers can be up to two metres deep with four, five or even six mines stacked one on top of the other.

Prohibitions For The Use Of Landmines

Although international humanitarian law and treaty law have provisions to regulate the use of weapons such as AP mines, they are often ignored.

The 1949 Geneva Conventions apply to all states, irrespective of treaty obligations. The Conventions stipulate that warring parties must distinguish between civilians and combatants, and refrain from using indiscriminate weapons whose “damaging effects are disproportionate to their military purpose.”

The 1980 UN treaty on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) has a further set of particular prohibitions for the use of landmines.

Protocol II of the CCW specifically bans: the use of mines when directed at non-military civilian targets; the laying of minefields without accurate records being kept; and the use of remotely delivered mines, unless their location is accurately recorded or they are fitted with a self-neutralizing device. The Protocol also specifies that once hostilities cease the parties are “to take the necessary measures to clear minefields.”

Protocol II, however, has had little or no effect on the use of AP mines in recent conflicts. Critics point to the CCW’s many weaknesses as the problem. “Protocol II wasn’t taken seriously. The use of so-called ‘smart’ mines, mines that are supposed to automatically deactivate after a specific time, made a mockery of the CCW. There is a 10 per cent failure rate, leaving thousands of active mines in the ground long after the neutralization date,” said Simon Gue, coordinator of Motivation, an NGO based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital.

In response to the increasing number of mines being laid, and to the number of civilians being killed or maimed, the UN convened a review conference of the CCW in May 1996. The results were disappointing, with the notable exception that the treaty now covers internal conflicts.

The Ottawa Declaration

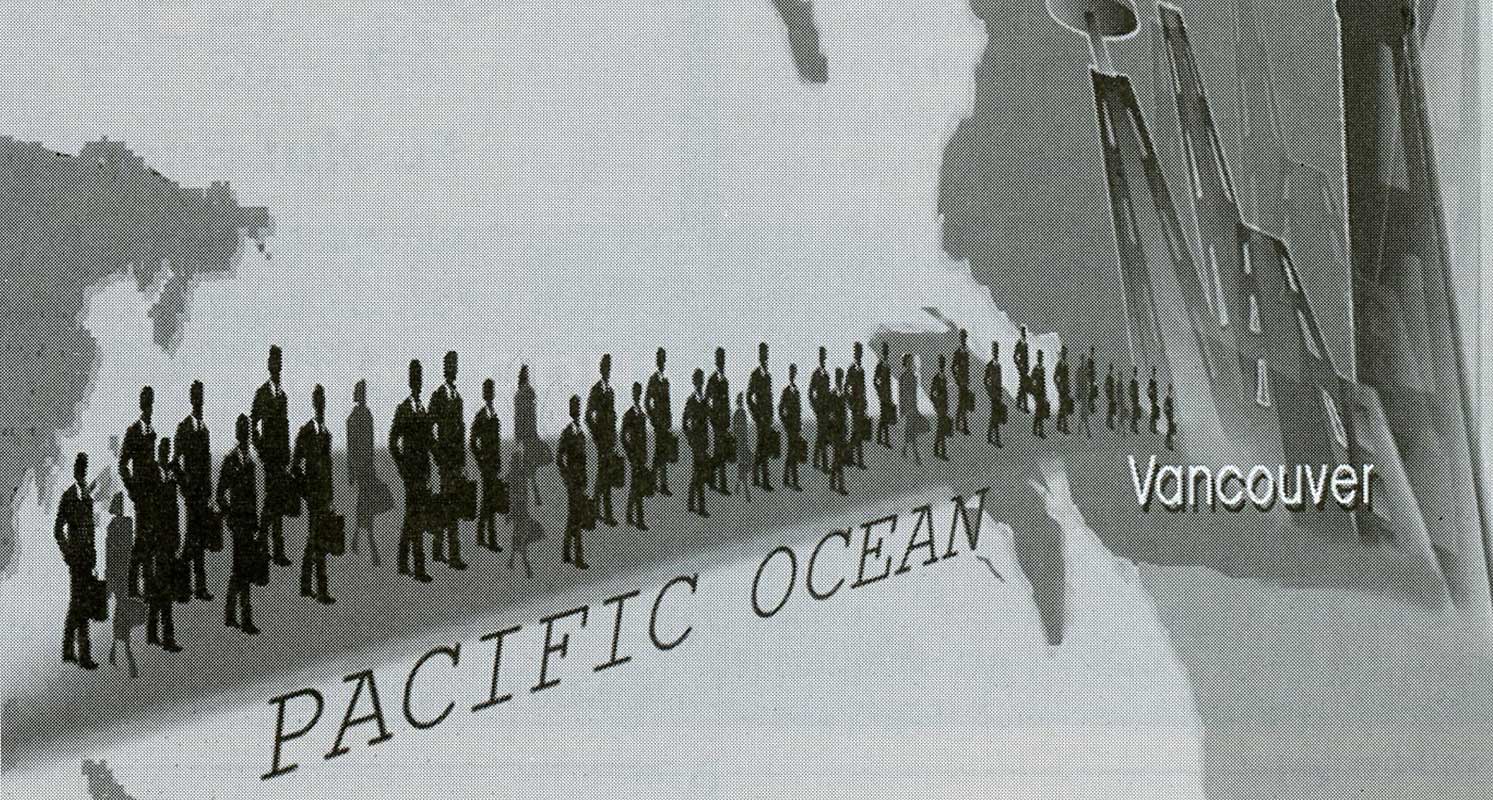

Last October, Canada invited 50 states to Ottawa with the intent of increasing the pace of negotiations for a landmine ban. They endorsed the Ottawa Declaration committing themselves to “work together to ensure the earliest possible conclusion of a legally binding international agreement to ban anti-personnel mines.” The Ottawa Process does away with the need for consensus, which dogged negotiations done through the CCW.

The 156 nations of the UN General Assembly passed a resolution in December calling on states to complete negotiations “as soon as possible” for an effective agreement to ban the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of AP mines. The resolution, however, is not a treaty and is not binding. It is the beginning of a process that could take years to complete.

What Is Needed For An Effective Agreement

In order for any agreement to be effective, it must be endorsed by the right states-namely, the Great Powers (i.e., France, Great Britain, the United States, Russia and China). So far Russia has only paid lip-service to the Ottawa Process and China has ignored it. China and Russia produce more than half of the world’s AP mines.

The United States is split. “The U.S. State Department wants to follow the Ottawa Process, a fast-track process, but the Pentagon would rather take it slow. They’re a little unwilling to give them [AP mines] up,” said Bob Lawson of Canada’s Non-proliferation, Arms Control and Disarmament Division.

The Conference On Disarmament

The Great Powers and many mine-manufacturing countries shied away from the Ottawa Process. Instead, they favoured attempting to get a ban through the Conference on Disarmament (CD), convened primarily to deal with chemical and nuclear weapons.

The CD consisted of 60 states, none of whose populations faced a landmine problem. Each state had a veto, and in order to get any kind of ratification there had to be a high level of consensus.

“The Conference on Disarmament is a very slow process. It doesn’t include the countries that are the most mined. The CD is a stalling process,” said Celina Tuttle, spokesperson for Mines Action Canada, an NGO pressing for a ban.

The Conference closed in March without any debate on the AP mine ban. “No one expected it to make it to the agenda. We expected it to fail from the beginning,” said Lawson.

It’s A Slow Process

Canada will reconvene the Ottawa Conference in December of this year with the hope of getting more than 100 countries to commit to a comprehensive AP mine ban.

The next step toward that will be a June meeting in Brussels to “take stock of progress” achieved since the process started in January 1996.

“Brussels will be a break point,” said Lawson. “The real thing to watch will be to see which countries are serious about a ban, and which ones intend to be disruptive.”

To date, 57 countries have explicitly endorsed the Ottawa Process. “The key ingredient in the Ottawa Process is the shared determination to establish an international norm, and not let the pace of negotiations or the content of a treaty be dictated by those who oppose a ban,” said Lloyd Axworthy, minister of foreign affairs.

It’s too late for Son Ngoc Samouth. His life has changed forever.

Because of his disability he has been forced off his farm. Unable to work the fields, and therefore unable to make a living, he had to sell his land. The money is now gone, and his wife has moved back with her family.

Today, Samouth ekes out a living in Phnom Penh. He sells cigarettes, Chiclets or anything else he can get his hands on. He lives on the street, making his home down a deserted alley among old trash and broken bottles.

Samouth was lucky, he lived. But in a country where landmines outnumber people, how many will be so “lucky”?