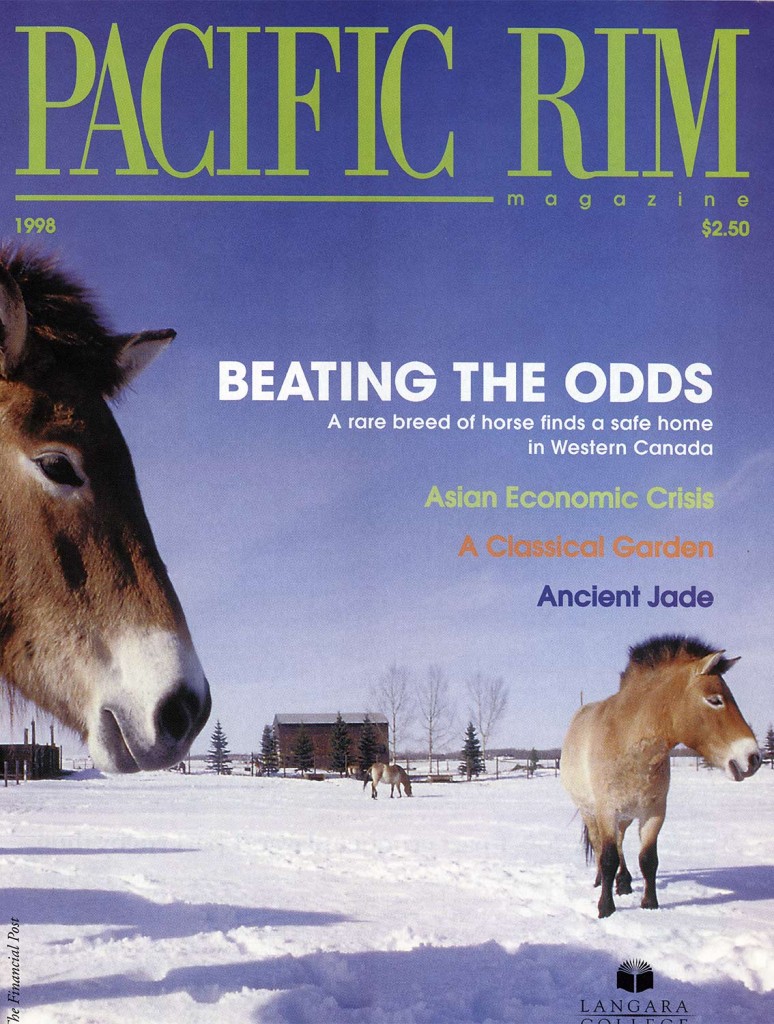

As I approached the two charismatic Asian wild horses that I had travelled four and a half hours to see, I wasn’t sure if they were sizing us up or simply inquiring where we were hiding their morning food rations. The latter proved to be closer to the truth. When Kamloops Wildlife Park zookeepers Richard Maze and Brett McLeod revealed the food barrels, the rodeo began. Belgan and C12 began kicking at each other with such violence that I was surprised neither was injured during this display of aggression. According to Maze and McLeod, this kind of horseplay is the norm for wild horses. In fact, if the two were to exhibit the more placid disposition of their domesticated cousins, it would be time to call a veterinarian.

The Przewalski Horse

The behaviour of the Asian wild horse, more commonly known as the Przewalski Horse, is not its only defining feature. Their brush-like upright mane begins just behind the ears and extends to the top of the spine. Their disproportionately large heads and necks make them appear clumsy and awkward-certainly not the case as demonstrated by their antics during feeding time.

Like any species that has not been interbred, the Przewalski’s colour characteristics do not vary much. The body is a sandy tan to reddish brown, with white around the eyes and muzzle, and black lower legs, mane and tail. Their long, pointed ears can be moved around to localize sounds, and are also used expressively; pressed back against the head, they signal an impending attack.

An Almost Extinct Species Fights Back

The Przewalski is one of the rarest species of animal on Earth, with a current population of around 1,200, all but a few of which were born in captivity. With their status among the most critically endangered species in the world, it is miraculous that the Przewalski Horse exists at all. In the mid-sixties, the last known survivors, 13 of them, were removed from the wild, and if not for their unique DNA structure, they would have had no chance of recovering to their current population. There are only two living species of equid that possess 66 chromosomes: Grevy’s Zebra and the Przewalski Horse-domestic breeds have only 64. Without this unusual genetic advantage, the gene pool would have been too narrow and the effects of inbreeding would have prevented successful reproduction efforts. Even with this unique genetic coding, it was still imperative that an organized effort be put in place to oversee the management of all breeding programs throughout the world. Through the efforts of international groups such as The Species Survival Program for the Przewalski Horse, based out of the Bronx Zoo in New York City, and a meticulously maintained International Studbook, the species has been saved.

The Species Survival Program For The Przewalski Horse

The Kamloops Wildlife Park in British Columbia is one of three Canadian parks that have been granted membership into the survival program. The Calgary Zoo, and Toronto’s Metropolitan Zoo are also members. As in Kamloops, the Calgary Zoo’s herd of 16 horses is quite at home in the Canadian winter. The Kamloops program began in 1982 with the arrival of Belgan from the Calgary Zoo and C12 from San Diego. There have been as many as five horses in Kamloops since 1992, all of which have since been dispersed to other zoos to enhance the genetic variance of their stock. When discussing the role of the Kamloops Wildlife Park with Education Director Bill Gilroy, the first question that came to mind was why Kamloops? According to Gilroy, Kamloops is one of the few places in the world with a climate and terrain very similar to the Przewalski’s natural habitat. From casual observation, the present site does not look big enough to comfortably house any more horses. “Acceptable living conditions for the animals” says Gilroy, “is of primary importance for a Zoo to qualify for entrance into the program. The requirements demand all animals must be properly fed, kept in a large enough space, and in a clean and safe environment. Unfortunately, the budget just isn’t there for more horses.”

Presently, little information regarding the various Przewalski survival programs around the world is available. Three herds were released in the early nineties. Accurate information on the Xinjiang-Uyghur release in Chinese Mongolia has proven impossible to obtain. Officials with the Hustain Nuruu Nature Reserve in free Mongolia claim that their horse population has steadily increased since 15 were reintroduced in 1992. According to Dr. Tserendeleg of the Mongolia Association for Conservation of Nature and the Environment, there are now 48 Przewalski horses in the Mongolian park. Even more encouraging is a report that later this year, another 20 horses will be brought to Hustain Nuruu from the Netherlands.

In the wild, the horses face the same dangers as any other animal; they too can succumb to disease, predation, extreme weather and poaching. Ironically, the very factor which fostered such a remarkable comeback is also a significant threat to their existence in the wild. Due to the unique nature of their DNA, coupling with other free roaming horses may be the greatest threat of all; unless the Przewalski Horse breeds with members of its own species, the bloodline that has made it possible to bring it back from certain extinction will be diluted and eventually lost.

But talk of extra chromosomes, natural habitats and studbooks is lost on Belgan and C12. They eat, oblivious to the fact that they may well be part of one of the greatest comeback stories ever written. It will take more than dedication and even luck to ensure the continued survival of the Przewalski Horse, but with the help of the Kamloops Wildlife Park and other organizations, one of the earth’s oldest inhabitants will certainly see the light of a new millenium.