Rain streams steadily on another grey afternoon in Vancouver’s Chinatown, where the streets are always brimming with activity. Grocers arrange large piles of produce; butchers take smoke breaks while still wearing white, plastic aprons; and elderly women drag their shopping carts along the sidewalk. Chinatown is a centre for Vancouver’s Chinese community: a place to find food and traditional medicine, and a place where elderly Chinese people feel comfortable and can speak the language. It is also a place where the grocers, bakers, and butchers provide inexpensive food options to low-income people in Chinatown, the Downtown Eastside (DTES), and Strathcona.

Chinatown is rapidly disappearing as developers snap up properties and build new condo developments and high-end retail spaces. Many of the old storefronts and markets are closing their doors, replaced by boutique food, retail, and coffee shops. Housing costs have also risen. The increased popularity of the area is causing renovictions: in Chinatown, this means that single-room occupancy buildings that used to cater to people with fixed and low incomes are now being renovated and converted to artist and student housing (often at twice the previous rate). Chinatown is changing quickly, and though many believe this change is inevitable, there are groups within the community fighting to preserve the neighbourhood for the Chinese and low-income residents.

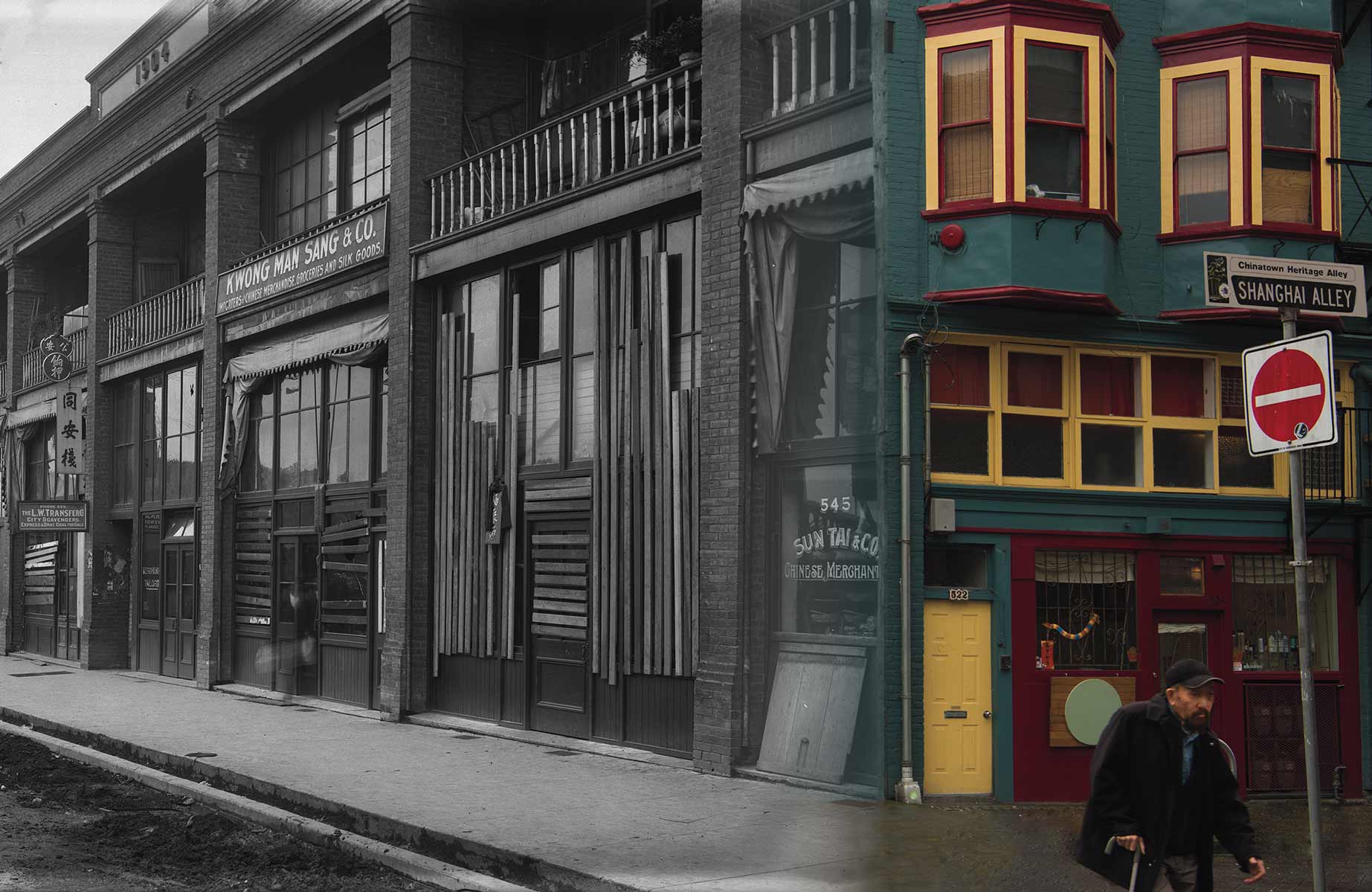

Vancouver’s Chinatown was formed in 1886, partially as a result of discriminatory practices that prevented “Asiatics” from owning property in other parts of the city. These prohibitions pushed Vancouver’s Chinese population into Chinatown, where many felt a sense of safety and community. Between 1890 and 1920 Chinatown flourished, despite a head tax of $50 to $500 per person entering Canada from China. However, due to what is commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 and the Great Depression, Chinatown began a period of decline.

In the sixties, the City of Vancouver began forging urban renewal programs that would expropriate and demolish most of Strathcona (a residential neighbourhood just east of Chinatown). The first part of the redevelopment plan, according to David Chuenyan Lai’s book, Chinatowns (1988), included the displacement of 4,500 mostly Chinese residents by, what was then called “slum clearance.” In response to this plan, grassroots organizers formed the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) in 1968—a multi-ethnic community effort—to fight against the City’s expropriation of land in Strathcona. According to Lai, residents organized against the City’s plan, arguing “that the social impact on the community had not been considered.”

Jo-Anne Lee, PhD, explains that Strathcona used to be “a very diverse neighbourhood.” Lee resided in Strathcona during the time that SPOTA was active, and has since dedicated much of her scholarship to analyzing SPOTA’s history and legacy. Lee recalls that, “many of [the residents] were not well-educated, and many were new immigrants. Yet they managed to stop a three level government-funded urban renewal program that was intended to bulldoze the area and force compulsory expropriation of homes, displacing people without providing any other form of accommodation. [SPOTA] organized, lobbied, and persuaded the government to listen, and to create a brand new neighbourhood rehabilitation program that became a pilot for the rest of the country.”

According to Lee, “business owners, clan associations [associations based on kinship, family name, or home village] and real estate companies,” supported the redevelopment plans that would displace thousands of Strathcona residents. She further explains that, “[this group was] trying to speak for the community… However, [SPOTA] wanted Strathcona to remain an affordable, low-income family neighbourhood. Members knew the developers wanted high-density housing projects in that area.” She believes that even today, “the residents need to claim their rights as citizens, that they are equal to anyone else. That is their democratic right.”

A New Revitalization Plan

Chinatown is home to many Chinese seniors who live on fixed incomes. They tend to live in single-room apartments, often with shared amenities. As these buildings age, many people argue that the area needs revitalization and that these buildings should be torn down and replaced. Regarding the older housing in Chinatown, Jannie Leung of the Chinatown Action Group states, “people say that they are falling apart and that they’re not safe. Then there’s all this language about trying to clean up Chinatown. Underlying that is the racially discriminatory idea that Chinese people are dirty, that Chinatown is a slum.” However, Leung says, “It was actually decades of neglect by the City that caused [this].” During the latter half of the twentieth century, the City of Vancouver’s disinvestment (lack of upkeep and investment) in Chinatown and Strathcona kept property values low. As housing availability across the city diminished, developers moved into Chinatown: 55.6 per cent of the housing in Chinatown was constructed between 2001 and 2006, compared to 8.9 per cent of all housing elsewhere in the city.

As of December 2014, the rate of market housing to social housing constructed in Chinatown was 71 to 1. The Carnegie Community Action Project (CCAP)—a community organization that works on housing, income, and land use issues in the DTES—has compiled a list of proposed building developments in Chinatown. This list tracks the number of suites renting at market prices versus the number of suites available at the equivalent monthly housing allowance for people on welfare ($375 per month or less). CCAP has also made a Hotel Survey and Housing Report, which shows that between 2009 and 2014, the percentage of buildings renting all of their rooms for $375 per month or less went from 29 per cent to 9 per cent in the DTES (including Chinatown).

A multi-generational group of activists who self-identify as Chinese, known as Chinatown Action Group (CAG), are working with Chinese seniors living in Chinatown to fight against the risk of displacement and gentrification. They use the term “self-identified Chinese” because it allows people with complex Chinese identities (e.g. those who are third generation Chinese-Canadian or those who may not speak Chinese) to come together in a unified effort. Leung says, “[the City’s and the development companies’] idea of preserving Chinatown is putting dragons everywhere, but that’s not preserving Chinese people; that’s commodifying Chinese culture and presenting Chinatown as a tourist centre.”

The businesses that have been here for decades serving the Chinese and low-income community in Chinatown, Strathcona, and the DTES are rapidly disappearing, while condos and boutique shops and restaurants are being developed in their place. These changes are stripping away pieces of the Chinatown community until the neighbourhood is unrecognizable. But the fight for the community is strong and picking up momentum. Sid Chow Tan, a community organizer and Chinatown resident, describes this momentum as, “this generation’s battle for the soul of Chinatown.”