Emily Liu began practicing kintsugi when a friend asked her to mend a broken cup that held precious memories. Thanks to Liu’s background in dentistry, she was familiar with restoring porcelain, so she repaired the piece; however, she disliked the look of the finished cup and decided to embellish it using the Japanese technique known as kintsugi. Wanting to learn more about the craft, Liu studied under pottery Master HiDe Ebina and kintsugi Master Asami at the Vancouver-based studio, HiDe Ceramic Works.

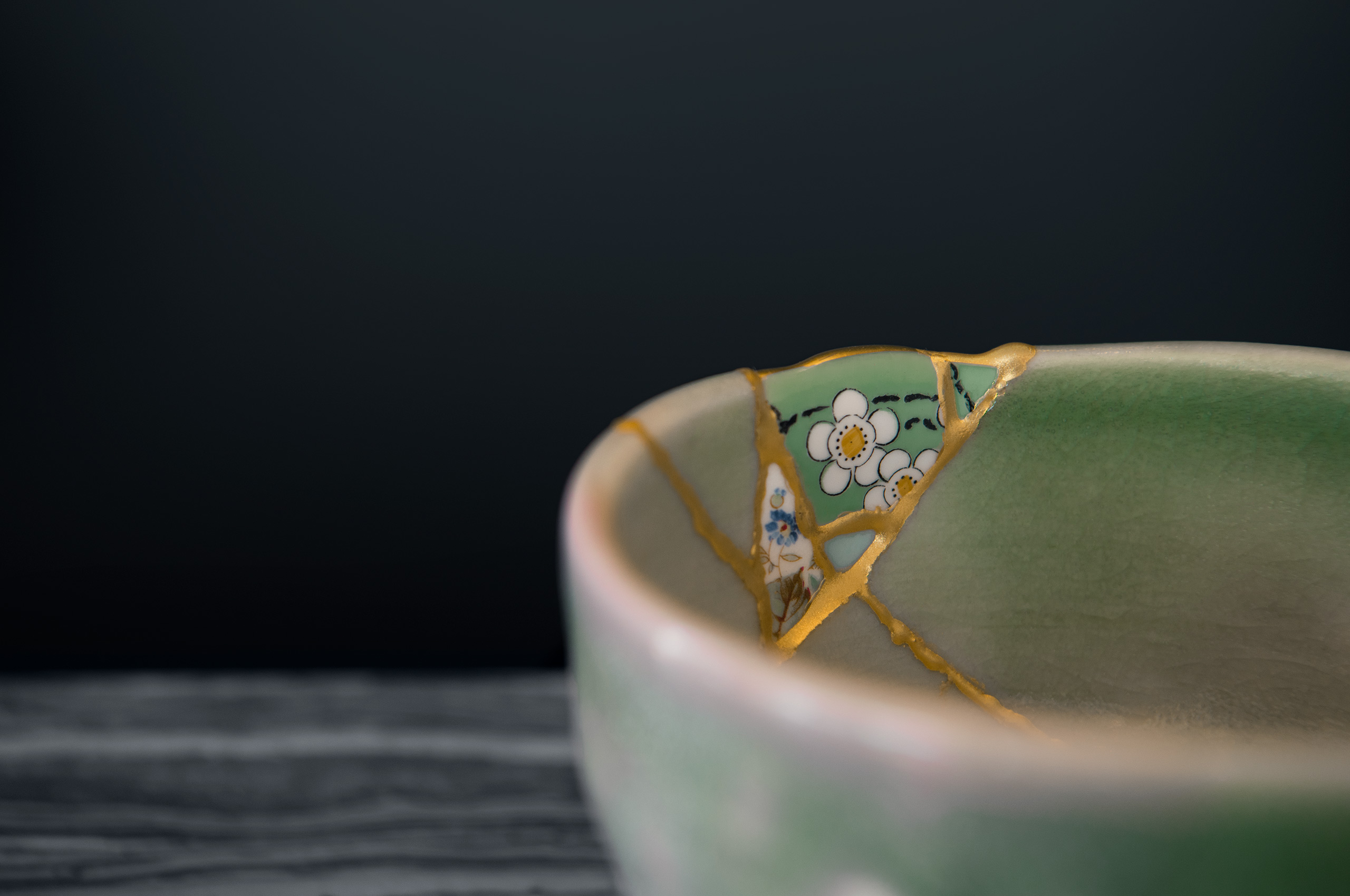

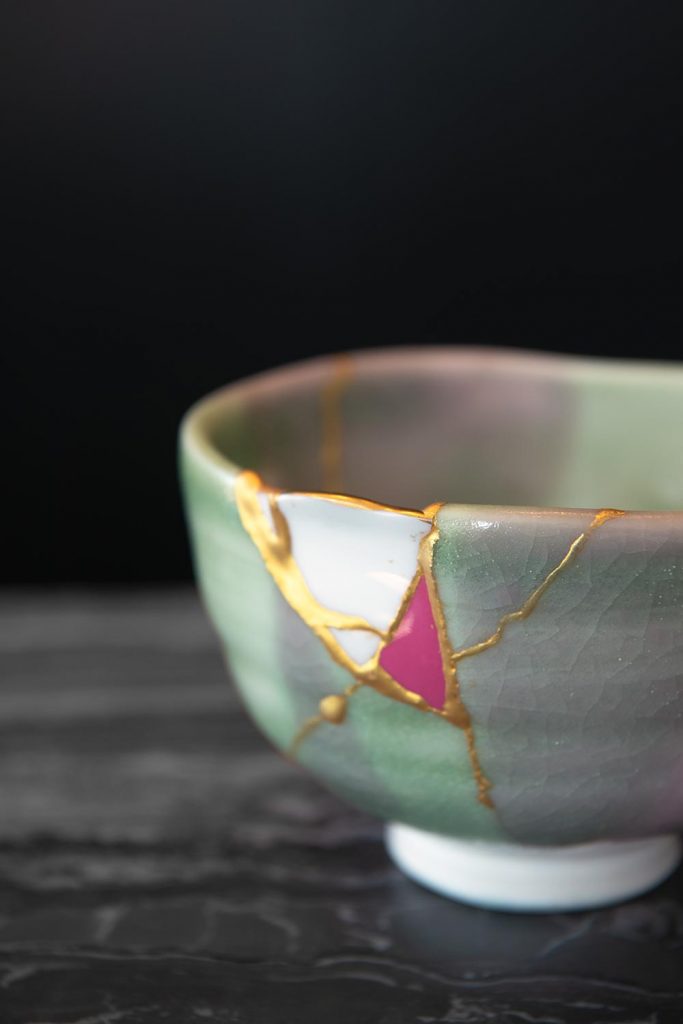

Kintsugi, which can translate to “gold joining,” is thought to have originated in Japan during the late 15th century. The process was first used to mend objects of great importance, such as bowls and utensils that were “the central components of the Japanese tea ceremony,” explains Rebecca Cragg, owner of Camellia Teas of Ottawa. Kintsugi exposes the fractures in a broken object, highlighting them with gold as a testimony of its history.

The process begins by determining how to put the broken pieces back together. According to Dave Pike, an American artist living in Nara, Japan, it can take from ten minutes to an hour to decide how the pieces fit and how to approach the mending. Once this step is complete, multiple layers of lacquer are used to fill in the cracks, and finally gold or other metals are painted overtop.

Most kintsugi artists agree that it is a time-consuming process. Liu explains that 200 to 300 layers of lacquer must be applied, and each layer must dry for anywhere from 7 to 12 days before another is added. In Liu’s experience, it can take a month to six months to finish a piece. “You need a lot of patience,” she says. “It’s fine work. If you rush it, it’s not art. I can give it to you in a week if you use superglue and paint gold on it, but it’s not the same as kintsugi. I’ve never had a person say, ‘Oh, I can’t wait that long.’ They understand that you have to take time: you have to do it right.”

However, kintsugi should not be applied to just any object. “The purpose of kintsugi was to repair something of value and sentimental worth, so that you could continue to use it,” says Cragg. According to Liu, such emotional value means “you’re willing to spend hundreds of dollars to fix something that might have only cost fifty dollars in the first place.”

Despite the tradition behind kintsugi, Cragg has noticed some of her clients see it only as a decorative art form: “People in the West are being drawn by this notion of the broken being beautiful… So I’ve had, for example, clients come to me and say things like ‘I really want to learn how to do kintsugi,’… and they’ll come in with nothing broken and shatter something on my floor!”

Cragg emphasizes the importance of an emotional connection with the broken item when performing kintsugi. She tells the story of one of her clients whose wife had bought a beautiful, blue salad bowl when the couple lived in Germany. The bowl was always on the table as a centrepiece; it was part of the family. Unfortunately, the bowl was broken in a move back to Canada. The client explained that his wife was so devastated that she could not even bear to see the pieces, so he stored them in a box in the garage. The pieces remained there for 15 years.

By chance, this client came across the concept of kintsugi and learned about Cragg’s work. So, he took the box with the bowl pieces to her studio—without telling his wife. Cragg was in tears after she listened to the story and said, “I can, of course, repair this bowl for you, but there is no way that you’re not [going to be] a part of the repair of this item because it’s way too important.”

After six months of work, Cragg’s client gave the blue bowl to his wife as an anniversary present: “For an hour and a half,” says Cragg of the wife’s reaction, “all she could do was hold that bowl in her arms… and it was the most amazing, touching moment… this is what kintsugi is about.”

Apart from being a deeply personal process, kintsugi can be therapeutic as it requires full awareness and attention to detail. An individual must be mindfully present while filling in the cracks of a broken item. For some, it can feel like filling in the cracks of their heart. One of Cragg’s clients had a son who died in a car crash. Around the same time as the accident, the client’s favourite ikebana (floral arranging) bowl had broken. The client worked alongside Cragg, repairing the bowl near the anniversary of her son’s passing. “For her, it was not about it looking good by the end of it—it was simply the task of piecing it back together,” Cragg recalls. “I asked her, ‘How did it feel doing this?’ and she cried and said, ‘I feel like I put my heart back together again.’ ”

Whether it is restoring an item of great value, or the process of finding mindfulness, kintsugi is an art form that provides the artist with something meaningful. After all, “kintsugi is a very potent, emotional experience,” Cragg says, “if we allow ourselves to engage with that dimension of it.”