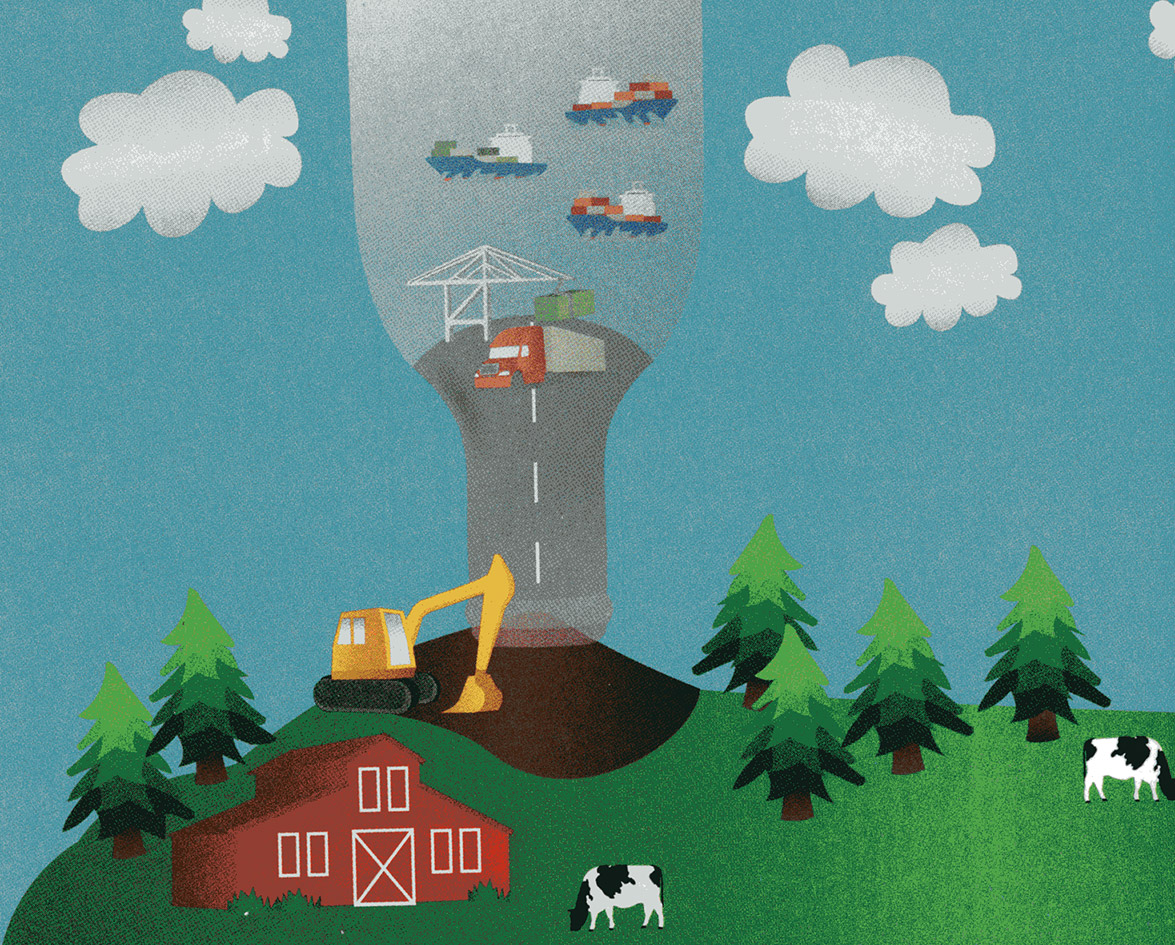

Vancouver’s stunning North Shore mountains, sandy beaches, and pristine parks bring visitors from all over the globe. On the surface, tourism appears to be the economic engine driving the city, but at the water’s edge, behind the postcard vistas and dramatic skyline, lies Vancouver’s true economic workhorse, the Port of Vancouver.

Gantry cranes that look like skeletons of giant giraffes hoist 20- and 40-foot cargo containers onto ocean liners coming from all over the Pacific Rim—China, Japan, and South Korea. Twenty-four hours, seven days a week, trucks and trains come and go with trailers, reefers, and boxcars filled with the goods that keep the money flowing. The buzz of high-tech forklifts and constant crackle of intercoms drown out the cries of Vancouver’s ubiquitous seagulls. Tourism may get all the glory, but the port is the city’s crown jewel.

In many ways, the Port of Vancouver is the little port that could. Smaller than many of its West Coast rivals, the Port of Vancouver competes at a world-class level. In 2001, it shipped just under 73 million tonnes, a greater volume of goods than any other port in North America. Last year, over a million containers alone passed through the port. The numbers are impressive, but Vancouver’s Port Authority and other business groups argue that unless changes are made to the Canada Marine Act, trade will go elsewhere. The Port Authority now has the opportunity to make its case at the Canada Marine Act Review and has identified key areas the federal government needs to address.

What Did The Canada Marine Act Do For The Port Of Vancouver?

When the Canada Marine Act became law in 1998, it commercialized 19 of Canada’s ports and established the port authorities to manage them. The goal was modernization, to create self-sufficient entities that could compete on the world market. The Port of Vancouver has, so far, been successful in that venture, but Robert Wilds of the Greater Vancouver Gateway Council thinks the federal government could do more to help.

“The initial Marine Act was a good piece of legislation,” he said. “It did a lot of good things, made a lot of changes that were required. Now it is time to fine-tune it.”

The fine-tuning is now under way with a review mandated to take place five years after the original Canada Marine Act received royal ascent. Transport Minister David Collenette began the process, appointing a four-member panel that held public hearings across Canada between September and November 2002. The panel has received submissions from port authorities, industry, port users, and other stakeholders. A final report will be completed by June 2003, with any amendments enacted by late 2003.

An agent of the federal government, Vancouver’s Port Authority is made up of nine members selected by government and industry, including former British Columbia Premier Mike Harcourt. It presides over 233 km of coastline and manages 460 hectares of partly unused land.

As the Canada Marine Act stands now, money made from the sale of port land must be sent to Ottawa where it is used as general revenue. Kevin Little, vice-president of business development at the Port of Vancouver, believes money generated from the sale of port land would be better spent facilitating trade, spurring more economic growth. “If we sell the land, the only reason we’d sell it is because it’s not useful for long-term port use, and we have a couple of pieces like that,” said Little. “If [the federal government] doesn’t trust us to invest it wisely, then put it in a fund and that money can only be spent on port infrastructure.” The Port Authority fears its infrastructure will not keep up with the demands of the ever-expanding world markets, and business will go elsewhere. Currently, the port’s main competition comes from the Port of Seattle. According to Little, capital for infrastructure at Seattle’s port is raised through the sale of tax-exempt bonds. Furthermore, it is a taxing authority. Every house within the county pays an annual port tax, used to pay off the interest on the bonds. “Essentially, it costs them nothing to build their infrastructure,” said Little.

The Marine Act Decreases Vancouver’s Competitive Position

Though the Port of Vancouver isn’t likely to become a taxing authority, it would like to issue tax-free bonds. It’s one way to raise capital that rewards the investor. “You can’t invest in our infrastructure. As a Canadian, I would very much like to be able to,” Little added.

Vancouver Board of Trade’s chief economist, Dave Park, agrees with the Vancouver Port Authority’s position on the Marine Act. Park believes leaving the port to pick up the tab for property taxes on land the federal government owns is just another way the Marine Act erodes Vancouver’s competitive position. The port pays $5.5 million Cdn in property taxes to surrounding municipalities each year. “They’re paying taxes or their tenants are paying taxes; whereas, in the States, they would be receiving taxes, so you have a real tilt to the playing field.”

The Cruise Ship Business

The playing field is a competitive one, especially in the cruise ship business, which generated $177 million Cdn in wages, $228 million in GDP, and $508 million in economic input for Vancouver in 2001. Recently, the Port of Vancouver spent $90 million trying to keep pace with the growing cruise ship business by upgrading its Canada Place terminal and turning five berths into three to accommodate larger cruise ships.

But only so much can be done. The Marine Act restricts how much ports can borrow from commercial lenders. The Port of Vancouver is capped at $225 million Cdn. Park would like this kind of legislated disadvantage removed from the act, believing there are very real consequences to the policy. “The Port of Seattle is able to offer a major cruise line a deal they couldn’t refuse because they had the money to do so,” Park lamented. “They are taking away a significant piece of our cruise ship business next year by offering really attractive rates for berthing and subsidized office space.” According to the Port of Vancouver’s web site, Seattle is assessing a new five-berth terminal likely to draw from Vancouver’s business.

In a speech given to the Vancouver Board of Trade on October 24, 2002, Captain Gordon Houston, president and chief executive officer of the Port of Vancouver, spoke about the ramifications of maintaining the status quo. He said the port will come up some $500 million short of generating the $1 billion it needs to meet its growth targets for 2020. Houston would like to see the federal government view Canada’s ports as economic generators rather than revenue generators, referring to the annual stipend the Port Authority pays to the federal government, averaging five percent of gross revenue.

The stipend is seen as more money becoming available for the infrastructure, which could facilitate more trade. Kevin Little stressed these changes are to the benefit of their employees, their customers, and the Canadian economy as a whole. By meeting their growth targets by 2020, the Port Authority predicts the creation of 20,000 new jobs, adding $2.2 billion in wages and another $3 billion to the GDP.

To the politicians in Ottawa who will ultimately decide the future competitive position of Canada’s ports, Little said, “Remove the shackles, take the hand cuffs off, allow us to create an environment that attracts private sector investment. You’ve got to provide the infrastructure, the terminals, the back up, the access, and if you don’t, you leave them no choice but to go somewhere else. You can’t stand still. If you don’t grow, then you lose what you have.”