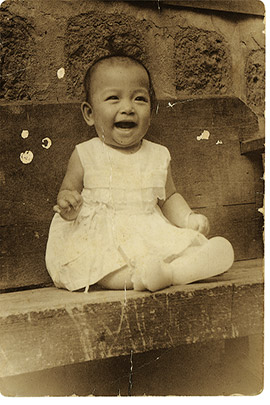

Marilou Tuzon stooped to put fuzzy mittens on a four-year-old blonde, blue-eyed little whirlwind of pink. Leaving a Vancouver community centre, both Tuzon and her “little buddy” called out goodbyes to their friends—other Canadian kids and the Filipino women in charge of them. Tuzon pulled on her own hood against the wind and, hand-in-hand, the two began the four-block walk to a treat of White Spot chicken nuggets and chocolate ice cream. As much as she enjoyed this moment, Tuzon missed spending time with her own four little whirlwinds growing up apart from her across the Pacific Ocean.

Filipino Nannies Wanted For Hire Internationally

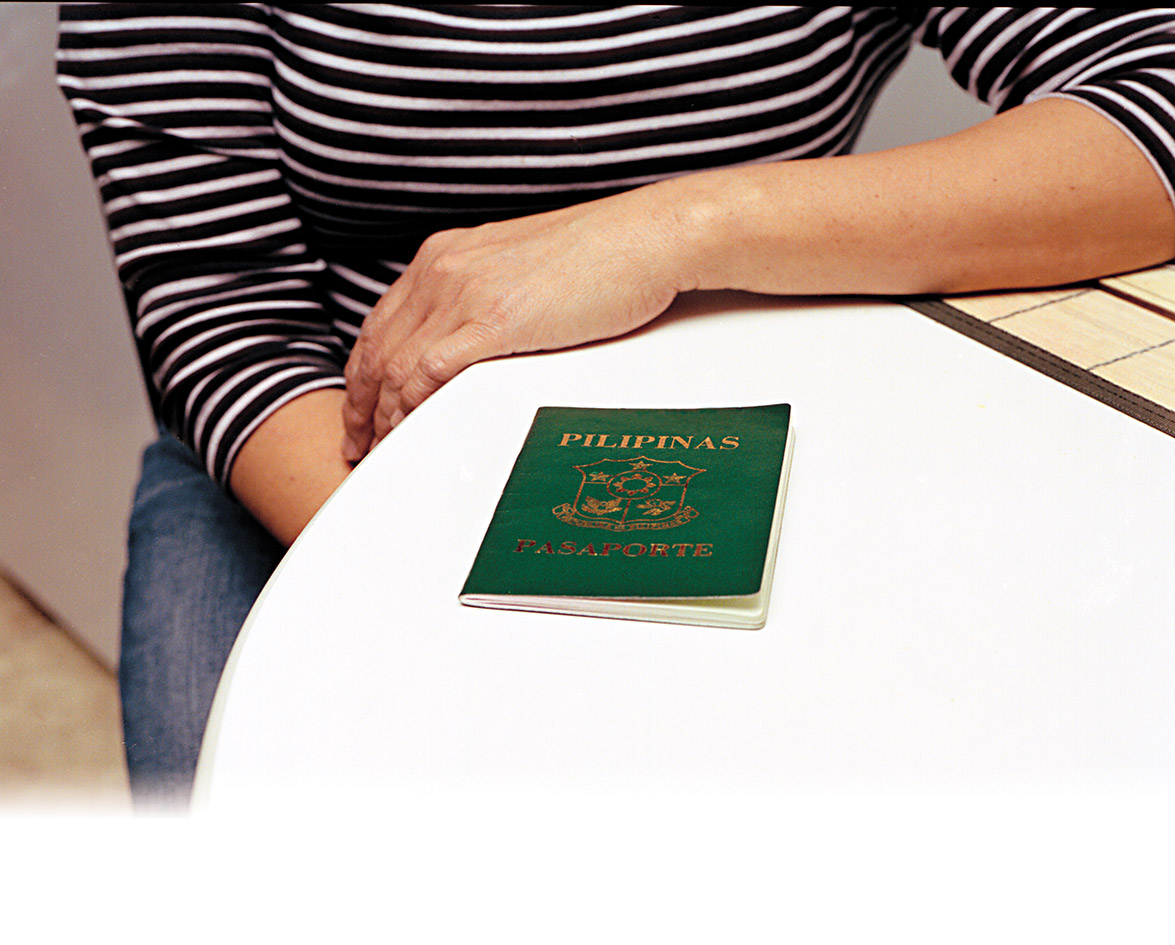

In Vancouver, seeing a Filipino nanny hard at work is almost as common as seeing someone toting an umbrella. Without a national child care system, hiring a live-in nanny from overseas is one child care solution for Canadian women who choose to return to work after having children. Filipino caregivers are in especially high demand. With approximately 4,000 Filipino temporary workers in Metro Vancouver alone, they are a familiar part of the city’s culture.

This Filipino phenomenon is nationwide. The majority of all foreign workers currently living in Canada come from the Philippines. Martha Scully, founder and owner of online nanny database CanadianNanny.ca, sees this trend played out in her business. “Of all the nationalities we have of overseas nannies, Filipinos are number one for sure: more than double any other nationality,” says Scully.

Canada may prefer Filipino caregivers, but so does the rest of the world. The Philippines is the world’s largest exporter of labour. Ten per cent of the Philippines’ population, approximately ten million people, live and work overseas, and there is a constant demand for more. The majority of Filipino temporary workers live in the Middle East and other parts of Asia, while up to ten per cent of overseas Filipinos work in Canada.

Rosemarie Edillon, Director of National Planning and Policy Staff for the Philippines’ National Economic and Development Authority, recognizes the migration of Filipino workers as a matter of supply and demand. “In the Philippines we have a very high level of human capital. And in other parts of the world countries are at an economically stable stage of development but don’t have as much human capital.”

In other words, the Philippines have people willing to work, and developed countries have money and are willing to pay. Much of the money made by overseas workers is faithfully sent home as remittances, enabling the Philippines to stay economically afloat while many of their educated citizens leave the country. Remittances create up to ten per cent of the Philippines’ GDP (about 22 billion CAD), making it the second-largest source of foreign capital for the country.

Why Filipino Nannies Are Popular

Parents love Filipino caregivers in part because most come to Canada with additional training like nursing and teaching—skills that would cost more to hire from a Canadian nanny. “So that’s part of the appeal,” says Scully. “Parents can get someone who is actually a nurse living in their home and pay them close to minimum wage.”

Most Filipino caregivers come to Canada with additional training like nursing and teaching-skills that would cost more to hire from a Canadian nanny.

Apart from additional training, Canada’s love for Filipino caregivers is tied to Filipino culture. “We learn from our families at a very early age to respect everyone,” explains Adelina Deloeg, a Filipino who worked the majority of her 17 years in Canada as a nanny. “That is what was put in our minds and hearts and that’s what we have to do from generation to generation. When you are growing up, everyone is caring for you—parents, uncles and aunts, all the extended family—and if we don’t have anything, everyone shares.”

Filipino Nannies Face Tough Choices

However, turning this caring into a commodity has a dark side that nanny Marilou Tuzon knows personally. As a social worker in the Philippines, she could not afford the medicine her husband needed when he was diagnosed with cancer in 2001. That same year, at the age of 37, she left her four kids, ages three to thirteen, with her husband and his family, and took a job as a nanny in Israel to support them. Tuzon furrows her forehead and looks down as she explains, “The situation was really tough for me. I didn’t want to watch him die without medication, and I didn’t want to see the kids starve.” For many Filipino nannies, homesickness is the greatest battle. “I became really numb. I needed to do this, so I didn’t think of myself anymore; I just thought about them.”

The transition was hard on her kids too. After Tuzon left the Philippines, her seven-year-old daughter always seemed to be sick. Trips to the doctor never revealed any problems, and doctors would send the little girl home with her relatives, saying, “She really misses her mom.” Geraldine Pratt, a Feminist Geographies professor at the University of British Columbia and author of Families Apart: Migrant Mothers and the Conflicts of Labor and Love, has spent 18 years researching the impact of overseas working mothers on their families at home in the Philippines. Pratt says what millions of Filipino children experience, we would classify as trauma.

Tuzon says with a small laugh, “Eventually she got used to it. And then started to say, ‘Buy me this, buy me that.’ I was sending a lot of money home for school and food and extras. I think as a mom you try to compensate for your absence.”

After two years in Israel, Tuzon applied to work in Canada under the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP), which allows nannies to apply for permanent residency after two years of full-time caregiving work. She chose Canada because the LCP made the process of sponsoring her family to join her easier than it was in other countries. “My hope was that if my husband passed away, at least then I could try to be with the kids,” she explained.

Tuzon moved to Vancouver in 2004, and three years later had just begun the process of applying for her family’s visas when she received a call from her husband. The cancer was spreading and he had been given two months to live. Knowing she wanted to be with her husband for his last two months, Tuzon quickly did the hard work of finding another nanny to fill in for her while she was gone. She got her papers in order and was on a plane to Manila in four days. Tuzon was on that plane when her husband died.

“I was so mad,” Tuzon says without apology. “I questioned God for that. I just wanted to see my husband and talk to him, and it didn’t happen. It took time before I accepted there was nothing I could do about it.” Tears still mist her eyes as she talks about it five years later.

Lasting Effects On The Family

Returning to the Philippines was not what Marilou had hoped either. “I was no longer connected to my kids. The children were not open to me. I was away from them for a long time, and we didn’t get used to each other.” She came back to Canada to continue working on her children’s visa papers and to keep sending money home, but life was not easy. “There were times I just wanted to curl up in a ball in the corner and cry, but you cannot do it because you have to go out and work.”

There were times I just wanted to curl up in a ball in the corner and cry, but you cannot do it because you have to go out and work.

Hundreds of thousands of families in the Philippines face conditions similar to Tuzon’s family. Women, mostly mothers—when faced with husbands who are sick, have died, or have gone to work overseas themselves and stopped sending money—set out to find a better life. They accept work in other countries, leaving children in the care of relatives. While the children may be cared for materially, “It’s still not the same as when a parent is there to look after the kids,” says Edillon, who worked with the Philippines’ government to study the impact felt by children left behind.

Pratt, in an interview with Society and Space, shares her own research: “What we find is that temporary labour programs are not so temporary: families are separated for seven to eight years on average, and the effects reach into the next generation.”

Almost 20 years ago the Philippines’ government recognized the impact overseas deployment was having on Filipino families and tried to limit the amount of people working out of country. However, the initiative never gained traction due to the economy’s reliance on remittances.

Once reunited in Canada, families often do not fare better than when separated. The transition is tough. “When it was just me in Canada, my life was work, work, work, and save money to send home,” Tuzon explains. “When my kids came here, I had to balance spending time with them and I still had to work hard. We didn’t get along. We barely knew each other.”

“Many of the children of domestic workers fare poorly in Vancouver after they migrate to join their mothers there,” says Geraldine Pratt. Her research shows, like many immigrants, Filipino children and youth experience displacement and feel like they do not belong. Filipino youth in Vancouver drop out of high school more than all other non-Aboriginal youth. In fact, Pratt found that Filipino children who immigrated between the ages of 12 and 16 ended up with lower levels of education and fewer job skills than their mothers.

As she reflects on the decision she made to leave her family, Tuzon has mixed feelings. “My kids would say, ‘Who told you to go? We didn’t tell you to go. You wanted to do it.’ It hurts me a lot. They wish I hadn’t gone. There were times that I wish I hadn’t gone, but now I think it’s still better than it would have been in the Philippines.”

Change For The Future

These stories of strength and brokenness are inextricably linked with Canada’s own story, one beginning to take a turn. When reports surfaced in the mid-to-late 2000s of Canadian employers taking advantage of Filipino live-in caregivers, Canada implemented stricter guidelines to insert more employer responsibility into the LCP. As a result, the numbers of those entering the program from the Philippines has decreased since 2007.

Also, the Philippines’ economy has begun to stabilize for the first time in 30 years. The country’s GDP has increased at a faster rate than their gross national income since 2011. This trend is predicted to continue, which is a good sign the Philippines is becoming less dependent on remittances and developing a robust economy of their own. “For the first half of 2012, there were about a million people awaiting deployment,” Edillon shares from the Philippines. “Now, that’s already a big figure, but if you compare it with the same time last year, it’s actually 35 per cent lower.”

This past August, in light of their improving domestic economy, the Philippines’ government initiated a five-year plan to slow overseas deployment. Still in the conceptual framework and development stage, the initiative aims to provide ongoing education and training for Filipinos, as well as liaise with agencies to find and create work opportunities for already-educated citizens at home. If all goes as hoped, the Philippines will be able to switch its focus to trading commodities rather than people.

If all goes as hoped, the Philippines will be able to switch its focus to trading commodities rather than people.

As Filipinos remain at home and Canada’s supply of patient, loving, Filipino caregivers dwindles, many Canadian families are left to ask, “Who will care for our children?” Without a national child care system, the options are limited. We may just have to invest in cultivating a patient and loving culture of our own.